Reading time: About 3 minutes

When you write, do you begin by taking an inventory of all the stories you have at your disposal? Here’s why you should try to collect as many as you possibly can…

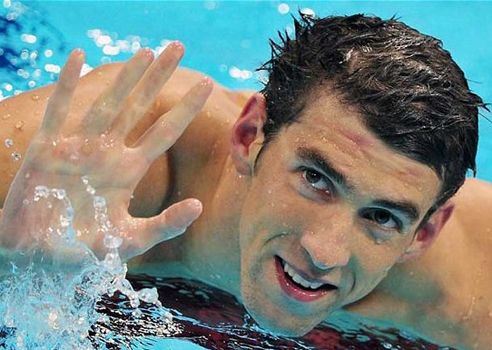

Let me begin by telling you a story. It dates back to the 2008 Summer Olympics, when Michael Phelps (pictured above) was churning water in the pool. In one race however, he had a problem. There was moisture inside his goggles. By the third turn in the final lap his goggles were completely filled with water and he couldn’t see a thing.

Here is what writer Charles Duhigg had to say about the incident:

The leaking goggles were a minor deviation, but one for which he was prepared. Bowman [Phelps’s coach] had once made Phelps swim in the Michigan pool in the dark, believing that he needed to be ready for any surprise. Some of the videotapes in Phelps’s mind had featured problems like this. He had mentally rehearsed how he would respond to goggle failure. As he started his last lap, Phelps estimated how many strokes a final push would require — nineteen or twenty, maybe twenty-one — and started counting. He felt totally relaxed as he swam at full strength.

Midway through the lap he began to increase his effort, a final eruption that had become one of his main techniques in overwhelming opponents. At eighteen strokes, he started anticipating the wall. He could hear the crowd roaring, but since he was blind, he had no idea if they were cheering for him or someone else. Nineteen strokes, then twenty. It felt like he needed one more. That’s what the videotape in his head said. He made a twenty-first, huge stroke, glided with his arms outstretched, and touched the wall. He had timed it perfectly. When he ripped off his goggles and looked up at the scoreboard, it said WR — world record — next to his name. He’d won another gold.

I knew the outcome of the story before I read Duhigg’s marvellous book, The Power of Habit, but the power of the story kept me reading. This is what good stories do and why I so strongly encourage all writers, even corporate nonfiction ones, to lard their work with stories.

I offered a workshop on this topic last week. My Extreme Writing Makeover group meets monthly to chat about writing and, in April, our topic was stories. I even read several excerpts from the Power of Habit to the group. My intent? To emphasize that a social-science-y book — one meant to be filled with notes, citations and tips — can still emphasize stories to its own advantage.

If you want to add more stories to your writing, here is some advice:

1) Know the best places to find the stories. If you speak only with VPs, you’re not likely to collect many stories. Here are some better sources:

- front-line workers

- customers

- retirees

- your company’s suppliers

2) Know that the skill in telling stories comes not so much from the writing, but from the interviewing. To be a storyteller, you first have to collect the stories. Collect good ones, and they will almost tell themselves. Fail to collect them? You will have nothing to say.

3) Make your interviews more like conversations rather than cross-examinations. People often ask me whether they should take a list of questions into their interviews. I always say yes — but with a catch. Don’t look at the list until the end of the interview. If you make your interview a conversation then your questions should always be based on what the subject has last told you. This will be more natural and engaging for your interview subject and you’ll collect better material.

4) Give your subject plenty of feedback. When someone tells you something interesting, say “Wow! That’s incredible.” When they tell you something that must have been distressing for them, say, “I’m so sorry to hear that. How did you cope?” Act like a human being rather than an automaton and the subject will be more inclined to tell you stories.

5) Don’t use superlatives. Questions involving the words “best, worst, most, easiest, hardest” are stressful for your interview subjects and may cause them to shut down while they evaluate. True, they’re tempting questions for people like us, because we think they’ll help us uncover the most fascinating stories of all. But they’re bad news for your subjects because they’ll be forced to perform rapid and difficult assessments — was that incident really the worst/best? Or was another one even more challenging/easier? Give them a break! Ask for one example of a difficult/easy situation rather than the most extreme one they can remember.

6) Ask for stories, anecdotes and examples. You don’t get anything unless you ask for it. So don’t expect your interview subjects to read your mind. Ask explicitly for stories. Also, be sure to use the phrase “stories, anecdotes and examples.” I learned this the hard way when I was working with a writer who failed to include enough stories in her work. I kept encouraging her to use more and she kept failing to do so. One day, out of sheer frustration, I said something like, “couldn’t you find any stories, anecdotes or examples?” She looked at me with a new understanding in her eyes. “Oh,” she said. “I didn’t know you’d wanted examples!” The problem was simply one of vocabulary. Don’t let the same misunderstanding arise with your interview subjects. Use a variety of words in the hope that at least one will mean something to them.

Telling stories — even very short ones — is one of the best techniques you can use to make your writing more interesting and more engaging to your readers. I suggest you make it a priority.

Where do you find the best stories for your writing? We can all learn from each other so, please, share your thoughts with my readers and me in the “comments” section below. Anyone who comments on today’s post (or any others) by April 30/16 will be put in a draw for a copy of Telling True Stories, a collection from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University. Please, scroll down to the comments, directly underneath the “related posts” links, below. Note that you don’t have to join the commenting software to post. See here to learn how to post as a guest.