Reading time: About 3 minutes

Do you have enough sentence length variation in what you write? The biggest problem? Most people don’t use nearly enough very short sentences.

Perhaps it’s time to consider the age-old question: does length really matter? I’m talking about writing, and sentence length of course. Let’s begin by taking a look at the approaches of two different authors:

The first is Daniel Gilbert, author of the bestselling Stumbling on Happiness. Here’s a brief excerpt.

This much we know for sure: Adolph Fischer did not organize the riot. He did not incite the riot. In fact, he was nowhere near the riot the night the policemen were killed. But his labor union had challenged the stranglehold that Chicago’s powerful industrialists had on the men, women, and children who toiled in their sweatshops toward the end of the nineteenth century, and that union needed to be taught a lesson. So Adolph Fischer was tried and, on the basis of paid and perjured testimony, sentenced to die for a crime he did not commit. On November 11, 1887, he stood on the gallows and surprised everyone with his last words: “This is the happiest moment of my life.”

The second is Michael T. Bosworth, author of Solution Selling.

By my definition of a benefit statement, however a seller cannot make a benefit statement initially with a buyer. The prerequisite for a benefit is a buyer vision in which the seller has participated. The prerequisite for that vision is that the prospect trusts the seller enough to admit a problem—and that the seller has the patience to avoid premature elaboration and can diagnose the problem. The prerequisites for a buyer to admit a problem to the seller are trust, sincerity, and competence. And the prerequisite for that trust is for that buyer to conclude the seller is different from most other salespeople. Once a seller has established rapport, sincerity, and competence and created a vision from an admitted pain, he can then take out his product or service and say, “I believe my product or service will fill that need for you.”

When I run these texts through readability statistics, here’s what I find:

Daniel Gilbert scores an average of 4.47 characters per word and an average of 20.17 words per sentence.

Michael Bosworth lands an average of 4.76 characters per word and an average of 24 words per sentence.

The numbers may sound close, but in fact, they’re a bit like the Richter scale. (If you live in Japan, New Zealand, California or British Columbia you immediately understand the tenfold difference between an earthquake rated six and one rated seven.)

I find Daniel Gilbert’s text to be infinitely more readable. It helps, of course, that he’s telling the story of a real person. This is so much easier to visualize than Bosworth’s more abstract scenario.

But it’s also relevant that Gilbert uses shorter words and, even more importantly, shorter sentences.

The people I coach sometimes beg me to let them use longer sentences. “Dostoyevsky did,” is the funniest argument I’ve heard. (If you want to be a famous Russian novelist, you need to be Russian. And a novelist. And famous!)

But most of us who write non-fiction are working to persuade busy, distracted people to read our work. The harder we make it for them, the less likely they are to want to try.

This is why short words and short sentences are so important. The aspect of the Gilbert text I like the best is the second sentence. It’s only six words. Six words! This not only serves to reduce his average (allowing him to get away with a few much longer sentences), it also gives his writing a compelling, seductive rhythm.

Smart writers aim for sentences somewhere between 14 and 20 words on average. Unfortunately, the best readability statistics calculator I’ve ever found (and it’s free!) gives only the overall average sentence-length for a piece.

But it’s urgent to understand that – within this average – you need to show sentences at a wide variety of lengths. Otherwise, your writing will be boring. And it won’t have any rhythm!

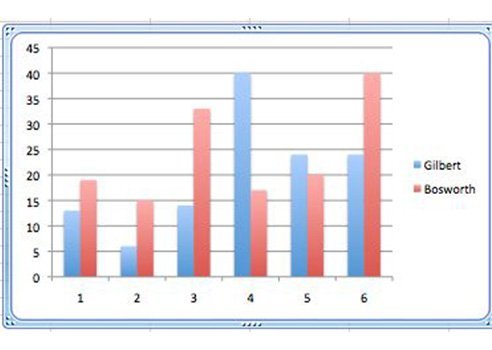

For this reason – even though it’s a bit tedious — it’s a good idea to occasionally calculate the individual length of your sentences in a piece. I took the trouble to do this for the Gilbert and Boswell texts, and here are the word-counts for each of their six sentences:

Gilbert: 13, 6, 14, 40, 24, 24.

Bosworth: 19, 15, 33, 17, 20, 40

Then I plotted them on a bar graph. Take a look at it at the top of this post.

My conclusion? Aim for a bar graph showing dramatic variation. And know that the more really short bars you have, the more really long ones you’ll be allowed.

Consider it your shot at becoming Dostoyevsky.

How does your sentence length measure up? (And if anyone knows how the label the axes of a graph in Excel version 10.2 please post below as well!) We can all learn from each other so please share your thoughts with my readers and me by commenting below. (If you don’t see the comments box, click here and then scroll to the end.)