Word count: 648 words

Reading time: About 2.5 minutes

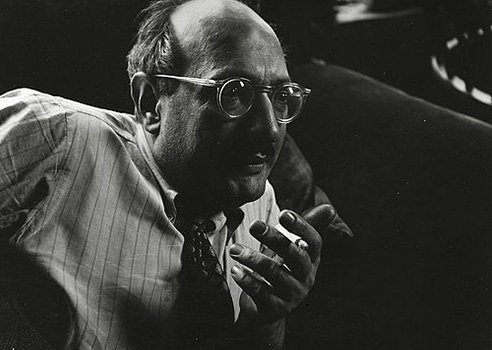

It’s interesting what people from different creative arts can teach each other. Here is a lesson painter Mark Rothko recently emphasized for me.

Six days ago, the only thing I knew about painter Mark Rothko, was that he was an abstract expressionist. (Here are some examples of his art.)

But I happened to be in Chicago last week –- teaching a writing workshop with Ragan Communications –- and on my one free evening, I indulged one of my favourite pastimes, seeing live theatre. The play I viewed was all about Rothko.

Written by Hollywood screenwriter John Logan (he wrote screenplays for Sweeny Todd and The Aviator) the play had four things going for it. It had received rave reviews; it was in a theatre only six blocks from my hotel; I was able to get a rush ticket at half price; and, it was only 100 minutes long — short enough for my jet-addled brain.

Actually, the show –- which was called Red — had five things going for it, but before I tell you about the fifth, let me give you a little background on Rothko.

Born Marcus Rothkowitz in Russia in 1903, he immigrated to Portland, Oregon when he was only 10 years old. Intellectually gifted, he learned English quickly and earned himself a scholarship to Yale University. But the Ivy League had rigid quotas for Jews in those days and Rothkowitz felt unwelcome. After only two years he quit university, moved to New York and discovered painting. It’s both sad and telling that he subsequently changed his name to Mark Rothko.

The story of this largely “talky” play centres on a 1958 episode in Rothko’s career when he received a substantial commission to create a series of murals for an upscale restaurant. In the play, he’s needled by his young assistant, to return the commission and keep the paintings himself, which he does. (The assistant was fictitious although the incident was true.) But here’s the part that surprised me:

About one-quarter into the play, Rothko turns to his assistant and says: “Painting is really THINKING. Only 10% of it is applying paint to canvas.” (Disclaimer: I am reporting this from memory and was unable to find a script against which I could check it.) The coincidence? This was part of exactly the same gospel I had been preaching in my workshop only that morning.

Just as most of us tend to see painting as applying paint to canvas, many of us also equate writing with moving fingers across keyboards (ideally, rapidly.) But, in fact, fingers-on-the-keyboard is only the middle stage of writing. You need to THINK, first. Even if an unruly boss is pushing you or your own insecurities are luring you to start writing, don’t rush too quickly to the keyboard. Madness that way lies!

Just as Rothko (or, to be accurate, the Rothko character in this play) said that painting is thinking, so, too, is writing.

As part of my workshop, I had all participants jot down the types of things they say to themselves while they’re writing. They came up with the usual batch of suspects: “I’m a bad writer,” “they’re not going to let me say this,” “this is too dull,” etc. But one woman produced a gem. “I’d rather be walking my dog,” she said to laughter from the crowd.

A few moments later, however, she speculated that this was probably something more helpful than harmful. I agreed. If you are having trouble writing, you may need to do some more thinking, first. Take a walk. Go for a coffee. Make a mindmap. Get yourself away from that keyboard and allow your ideas to percolate.

Writing interesting non-fiction requires creativity. And creativity demands a potent combination of thought and feeling – and, then, thoughts about those feelings.

If painters like Mark Rothko need to think, surely writers do, too.