Reading time: Just over 1 minute

I like to share interesting pieces of figurative language I encounter in my reading. I write today about a piece of personification from Kent Haruf…

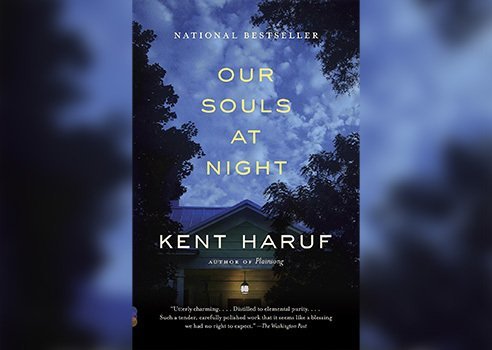

I just finished reading the sweet and lovely novel, Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf (pictured above.) The story of pair of senior citizens — a widow and a widower — living in small-town Colorado, it describes what happens when the two decide to spend their nights together, for talking and companionship.

Mostly very plainly written, the book has the occasional fillip, as in this amazing 193-word sentence, featuring clear, concrete writing and at least one example of personification:

The honor guard came first, carrying the limp wet flags and shouldering dripping rifles, then there were old tractors muttering up the street and old combines on flatbed trailers and antique hay rakes and mowers, and more tractors, puttering and popping, and the high school band, reduced in the summer to only 15 members wearing white shirts and jeans also can now and sticking to their skin, then the convertible cars with the country notables inside but with the tops up because of the weather, and then the rodeo Queen and her attendants on horses, the girls all good riders wearing ranch slickers, followed by more fancy cars with advertisements on the doors, and the cars from the Lions Club and the Rotary and Kiwanis in the Shriners zigzagging around in the street, like fat show off kids, on their hopped up go karts, and more horses and riders in yellow slickers and a pony cart, and toward the end of the parade there was a flatbed truck with a cardboard religious picture on it and a riser at the front, entered in the parade by one of the evangelical churches in town.

I don’t typically favour ultra-long sentences, but Haruf offers a master-class on how to pull one off. He does it by making the sentence almost entirely concrete and visual: the tractors, the antique hay rakes, the rodeo queen, the Shriners. Who hasn’t seen a parade like that? As well, he smartly places the verb right near the front — The honour guard came first — and it’s clear the rest of the sentence is essentially a list. Easy to read and easy to visualize.